An Anthropological Panorama

Durante años hemos esperado que la fiscalía

conozca nuestras historias, que oiga lo que tenemos que contar, que sepa como fuimos sometidas a esterilizaciones.

Inés Condori, Presidenta de la Asociación de

Mujeres Esterilizadas de Chumbivilcas.

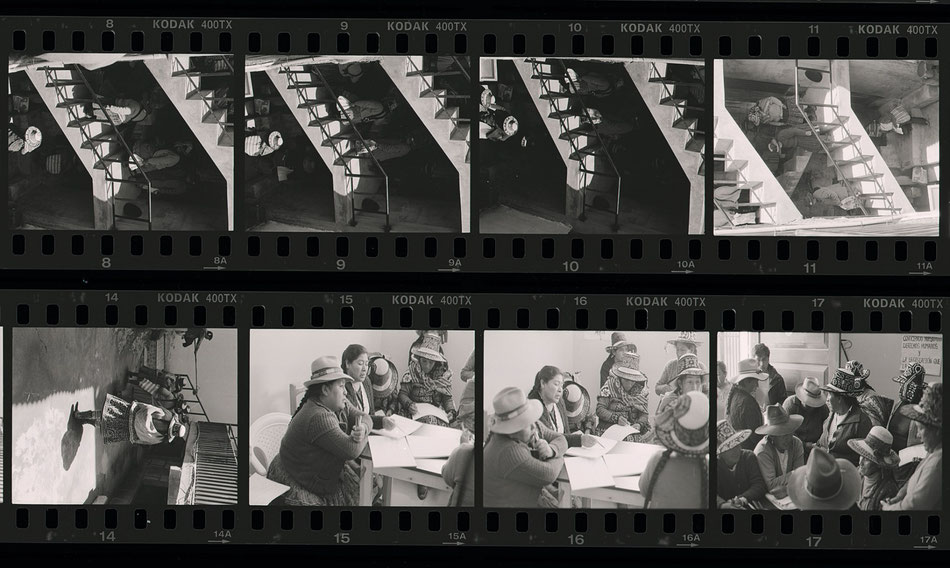

In recent years, many associations have been born in Peru with the aim of helping women who have undergone forced sterilization. Their main objectives are: reintegration into society of these women, obtaining justice and the distribution of health and psychological care.

One of these is represented by the Asociación de Mujeres Esterilizadas de Chumbivilcas, whose task is promoting a workshops project with the collaboration of Eduardo Villanes, a photographer and expert of visual arts. After specializing himself in the art of pre-colombine iconography and graffiti arts, Eduardo Villanes decided to organize these workshops where, sterilized women, meet each other once a week with the aim of getting to know themselves and use his drawings as a mean of expression.

The project has a strong anthropological and ethnological value: these women, with the material provided by Eduardo, mainly reproduce sombreros (hats) and symbols that represent the female

reproductive organ, a sort of gender-iconography. This laboratory has also a social background because, the photograph, tries to make them socialize with each other, helping them to

relax.

The intention will be to realize an exhibition whereby, Eduardo's professionalism, will be shown in an Art Gallery in October 2020, exposing his amazing shots about the Women of this

Association.

Comisión de la Verdad y Reconciliación

On August 28, 2003, the CVR delivered its final report, clarifying serious human rights violations committed between 1980 and 2000, during the internal armed conflict and the regime headed by Alberto Fujimori.

The CVR, which began its work in 2001 after the fall of the Fujimori regime and the restoration of democracy, provided a lot of information to the Peruvian judiciary, which was essential for several judicial processes, including convictions against Alberto Fujimori and the leader of Sendero Luminoso, Abimael Guzmán. It also demonstrated the essential role that racial and cultural discrimination against Andean and native populations played in the violent conflict: according to their calculations, more than 69,000 dead and missing, 75% had Quechua or other indigenous languages as their mother tongue. The commission also made recommendations to repair the victims, strengthen the rule of law and lay the foundations for a genuine reconciliation based on justice.

The CVR findings and recommendations' have found strong opposition from traditional political sectors and some local elites. Trials against people, accused that very serious crimes, are moving slowly; the task of repairing the victims does not receive the necessary attention, and the families of thousands of missing persons find inaction and indifference in response to their demands.

“The most conservative political class is irritated by the final report of the CVR. Surprisingly, in this they go hand in hand with the Shining Path, which also hates him. However, family members and human rights defenders do not give up their efforts. The final report has become a fundamental platform for the human rights movement, and a historical accusation against the exclusionary and the violent,” says Eduardo González, former CVR worker and director of the Truth and Memory Program.

This website is edited by:

Alessia Turi Denisa Cosnita Francesca Russo Martina Caradonna Natascia Bettoni

Questo sito è stato realizzato con Jimdo! Registra il tuo sito gratis su https://it.jimdo.com